On a warm summer night, you’re stretched out on a blanket in the grass gazing up at the sky. The patriotic sounds of John Philip Sousa’s “The Washington Post” march ring through the air. Overhead, red, white and blue lights dazzle and glow — bursting into shapes like fountains, flowers and flags. It’s Independence Day — a day that has been synonymous with fireworks since the founding of the United States of America in 1776, when future president John Adams wrote to his wife Abigail, suggesting the day be “solemnized with … illuminations” [source: APA History]. Of course, in modern times we know these “illuminations” as fireworks.

But oh, how fireworks have changed over the years since their invention — which is thought to have occurred in China or India about 1,000 years ago — alongside the discovery of gunpowder. The first fireworks came about with the realization that stuffing gunpowder into rolled-up paper or bamboo tubes and then lighting it would create a bang so loud it was thought to scare evil spirits away. The bang, in fact, was all there was to fireworks in the beginning, much like our modern firecrackers, keeping evil spirits away from births, deaths, weddings and new-year celebrations, among other events [source: APA History].

After Italian explorer Marco Polo brought gunpowder from China to Italy in the late 13th century, Italian pyrotechnicians learned to send firecrackers into the sky with the development of aerial shells, which used gunpowder to both launch shells into the air and then have them explode. Italians were also the first to add metal bits to the shells to create gold and silver sparks, and in the 1700s, Italian pyrotechnicians added metal salts to create other colors [source: APA History].

Those loud, spirit-scaring bangs have long since evolved into brilliant overhead displays, with shapes and colors that grow more elaborate with every passing year thanks to the myriad people — chemists, artists, firebugs, often entire families — who have devoted their careers (and sometimes their lives) to the development of a better, brighter show that literally provides more bang — and more beauty — for the buck.

To create these well-choreographed fireworks shows, not the loud bangs and sparklers people set off in their own backyards, chemists and pyrotechnic professionals “bottle stars” — in a certain manner of speaking. Let’s take a look at how they do it.

First off, we’re talking specifically about what are known as “display fireworks,” not the consumer products people buy at their local fireworks stand every Fourth of July (wherever it’s legal to do so, of course).

Display fireworks are used in the professional fireworks shows sponsored by cities and towns large and small across the world, often occurring on New Year’s Eve. At these shows, you might see peonies, the fountain-like bursts of colors that create the most common shape; brocades, which make an umbrella shape with a lot of trailing stars; or even hearts, smiley faces and flags [source: APA Glossary].

The pros create these shapes in a surprisingly simple way — although this doesn’t necessarily mean it’s an easy process. So, don’t try this at home, kids, because if not handled property, fireworks can cause serious injuries or death.

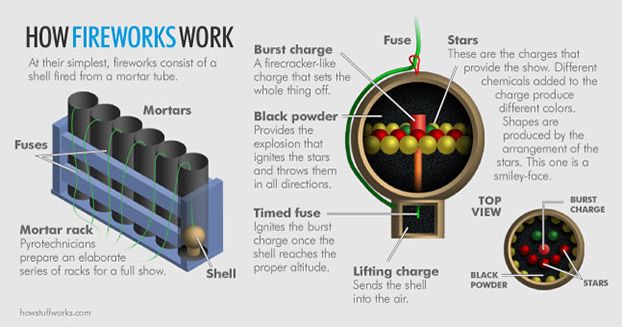

To create the aerial shells that make up display fireworks shows, small tubes are packed with explosive chemicals to create the desired lights, colors and sounds. Gunpowder makes up the majority of the material inside an aerial shell, along with smaller bits of explosives called stars, a bursting charge (think of something along the lines of a firecracker) and a fuse. When the fuse is lit, it ignites the bursting charge, which explodes, causing the whole shell to explode and light up the sky.

Aerial shells explode in two parts. First, the shell must be shot into the air so that the lights explode above the heads of onlookers, rather than on the ground. This is similar to a rocket being shot into the air. You need an explosion on the ground to send it soaring. To achieve flight, a tube called a mortar is set on the ground or partially buried in sand. Gunpowder with a fuse attached is placed inside the mortar. The shell is placed on top of gunpowder. When the fuse is lit, the gunpowder explodes, creating enough heat and gas to propel the shell into the sky [source: SciBytes].

In just a few seconds, the shell is high enough that the time-delay fuse inside the shell ignites, causing the bursting charge to explode. This sets off the gunpowder, which causes the entire shell to explode, sending the stars in all directions and creating the shapes and lights of fireworks that we enjoy [source: SciBytes].

While all parts of the aerial shell are essential for producing the fabulous fireworks shows we’ve come to know, it’s the stars that are responsible for the “oohs” and “aahs” of mesmerized spectators. The chemical makeup in stars — an oxidizing agent, fuel, colorant and binder — along with the placement of the stars in the aerial shell, creates the specific shapes and colors. Pyrotechnicians use carefully selected chemicals — strontium carbonate to create red, calcium salts and calcium chloride to make orange, salt to create yellow and barium compounds and chlorine to create green. Blue — the most difficult color to create — is made up of copper compounds and chlorine to make up stars that will in turn create the specific shapes as the fireworks bloom across the sky [source: De Antonis].

To create the shapes, stars are arranged on a piece of cardboard in the desired configuration. If the stars are placed in a smiley face pattern on the cardboard, for example, they will explode into a smiley face in the sky. In fact, you may see several smiley faces in the sky at one time. With shaped fireworks, pyrotechnicians often set off several at the same instant to ensure the shape can be seen from all angles. Spectators with the cardboard lined up along their line of sight may only see a burst of light or stars rather than the desired shape. If several go off at once, one of them should be oriented correctly at the moment it bursts so the crowd can see the shape [source: Wolchover].

According to Julie Heckman, executive director of the American Pyrotechnics Association, the first shaped fireworks were used in the early 1990s in Washington, D.C., to welcome returning Desert Storm troops. The original shapes were purple hearts and yellow bows [source: Wolchover].

Shapes are also created for what are known as set pieces. These are fireworks that stay on the ground, forming a picture such as an American flag. Set pieces are built out of different colored lances — tubes four to five inches (10 to 12 centimeters) long — which are filled with chemicals to create different colors that burn for about a minute. Lances are set into frames or boards and lit all at once in any shape you can dream up — from flags to words. Set pieces are expensive to create and time-consuming to build, so they’re not seen as often as aerial fireworks [source: Fireworks Alliance].

So the next time you’re lying back enjoying the light show in the sky, think about the work, imagination and creativity necessary for creating fireworks. And who knows? Maybe next Fourth of July, you’ll be treated to an interesting, patriotic parade across the night sky — perhaps even accompanied by rousing renditions of “The Stars and Stripes Forever” or the 1812 Overture.